Skylines, Skyrides, and Skygrids

Published:

This blog post will focus on Skygrid, dabbling in Skyride and Skylines in general before talking about the specifics around Skygrid parameter selection.

Skylines, Skyrides, and Skygrids

Recently, our lab has been going through changes… To our skyline plots. In the past, our lab, as a rule, has stuck to the Skyride coalescent model. Our bread-and-butter has recently become second fiddle to a (not-so-new) kid on the block: Skygrid. Because many in the group were used to generalized skyline plots and Skyride, this led to some confusion in how these different nonparametric coalescent models work, what to consider when using them, etc. There’s plenty written on the topic, but much of it is not super accessible. So here’s my go at it, starting with a brief overview of the various nonparametric coalescent models before discussing some nitty-gritty elements with Skyride and Skygrid.

The vibes

First, what are we even talking about here? Models that allow us to estimate effective population size over time, which is a common outcome in fast-evolving pathogens, like HIV, Ebola, or SARS-CoV-2. Effective population size is an abstract measure that provides an estimate of population size from genetic diversity under an idealized reproductive model. When we look at this estimate over time, we can get a good idea of population dynamics, leading to the field of phylodynamics.

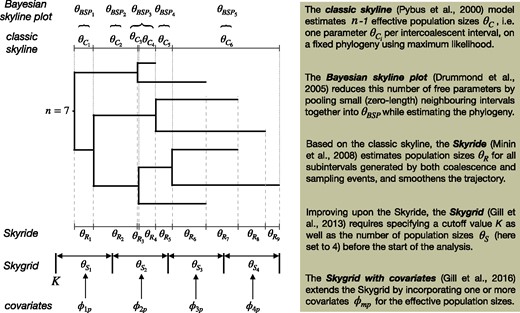

For a while, we were stuck with simple parametric coalescent models, like exponential growth or constant population size models. While nifty, these models were only useful if the sampled population fit those demographics. In contrast, nonparametric coalescent models offer a more flexible tool to enable estimation over time, giving us more accurate estimates of effective population size. This article by Hill and Baele provides an excellent overview of the different nonparametric coalescent models and a practical protocol for using Skygrid in BEAST. In particular, I’d like to highlight Figure 1 from their paper (below), which demonstrates the differences between classical skyline, skyride, and skygrid plots in a simple 7 taxa tree.

As you can see, the Skyline and Skyride plots both make use of variable-length bins of time for their demographic model. These bins correspond to the amount of time between coalescent events. In contrast, Skygrid leverages bins of equal size specified by the user. As a result, Skygrid, unlike Skyride or Skyline, requires a user to specify a cutoff value, K, (sometime before the first root of the tree) and the number of population sizes (i.e., how many time segments should it be divided into?). Both Skyride and Skygrid make use of a smoothing parameter. This smoothing prior considers all coalescent events and sampling times and uses them to smooth the population trajectory.

Nowadays, tutorials often promote Skygrid over Skyride because it allows for improved root height estimates, allows for multilocus data in estimates, and by estimating population sizes in real time intervals you can add in external covariates or link it to epidemiologically meaningful time points. The statistical properties of Skygrid have also been highlighted as a benefit, but that’s beyond both me and the scope of this little blog post.

How do we choose the number of time segments for Skygrid though?

One big downside to Skygrid is it makes us do work. Now, instead of having no parameters to tune (unless you include precision, which is recommended to be kept at the default, uninformative, prior), we have two whole parameters to fill in! We’ll start with the easiest, K. K is just a number larger than your overall tree height, which tells BEAST how far back to start the time intervals. You should use a quick maximum likelihood tree to get a rough guess for the root, and then take your most recent sample minus this likely root as your value of K (just make sure to add a bit of wiggle room! For example, if you have a SARS-CoV-2 phylogenetic tree, with samples collected up until November of 2021 (2021.92), since we know that the root of the tree is likely around the end of 2019 (2019.8), we should set K to around 2.3 or so (2021.92-2019.8+fudge) in order to capture that root and give it a bit of wiggle room.

The harder part is figuring out how many segments to use. This is dealer’s choice! Like with everything in statistical modeling, there are trade-offs and more than 1 right answer. As you increase the number of bins, you’re increasing the complexity of your model, slowing down your run and possibly leading to issues in getting your model to converge. In contrast, if you have too few bins, you might have too coarse of a look at your population dynamics.

I get it, I get it. That’s not satisfying. Here are some basic guidelines to get you started:

If you have too many grid points, or if your samples are clustered tightly together in groups, you may not have a coalescent event in each equal time interval… crowd goes silent as there’s an audible gasp This means your time segment is not identifiable (i.e., no data no results). Fortunately, that smoothing parameter does work so you won’t have “ack! No data!” and a crashed BEAST run. However, this may lead to null ESS values and meaningless estimates for that time interval. You should double check that your tree(s) have at least 1 coalescent event per interval. Ayo, we have an upper bound now: n-1, where n is your number of taxa if their entire evolutionary history miraculously lines up with your grid.

Ok cool, that’s better than nothing, technically, I guess. But do you have anything more helpful than that? Sure! Consider temporal constraints. Are your data collected by the second? Day? Month? If you don’t have temporal resolution high enough to resolve the number of grid points, it’s probably not worth doing. So in the previous example with SARS-CoV-2, if we were running with 1000 taxa over roughly 2 years, while we can narrow down to 999 grid points by the taxa rule of thumb, we can get this number down to 730 if we take into account our time resolution (daily collections of samples). If your sample collection dates are by month, then it’d make more sense to just use 24ish.

Again, this is not the best answer. That leaves between 1 and 730 time bins. Next, we take into account the less-tangible stuff. What makes sense? What resolution is needed for your analysis? What about your covariates? Are they measured at a monthly scale?

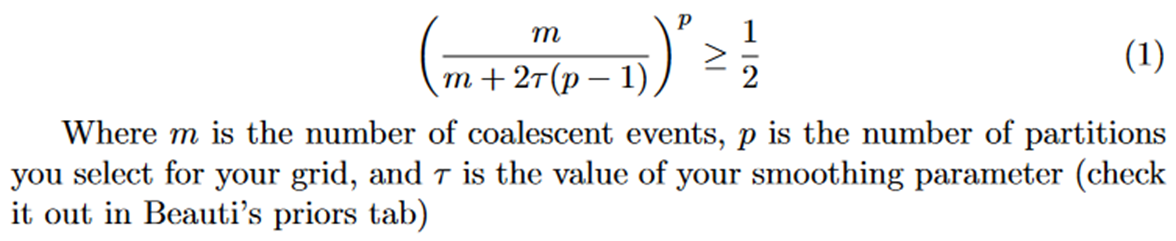

Another, more complex item to consider is smoothing. This is largely taken into account by an uninformative prior, Tau. However, there is a chance that this parameter ends up oversmoothing. That is, there is a chance that the smoothing parameter ends up smoothing in a way which overwhelms your data. According to Parag, et al., this is guaranteed for Skyride, and in Skygrid, could be avoided by transforming the prior. In lieu of that, we can do some quick checks afterwards with a formula they developed.

All this being said, there is no single right answer to the number of grid points to use. To help with oversmoothing and identifiability considerations, a colleague of mine, Gabriella Veytsel, developed a web app to highlight time segments without coalescent events and perform the omega calculation to see if your grid selections make sense. An alpha version of this app is hosted here: https://glstott.shinyapps.io/segmentation-finder/

Basically, you load your tree, plug in the values for K and number of segments, then it will visualize the tree, highlighting time segments without a coalescent event in red and letting you know if the omega estimate is at least 1/2, i.e., your inferred precision (aka tau) is low enough to prevent oversmoothing of your estimates.

Concluding thoughts

- Skygrid and Skyride are both great models! Even if Skygrid is becoming the preferred strategy for many, it has an additional trade off in the additional thought required to set it up.

- Skygrid has bins of equal size which are user-specified. In contrast, Skyride has bins equal to the number of intervals between coalescent events.

- When determining the best number of grid points, it’s important to consider whether you are getting enough grid points to capture important movements in effective population size.

- However, you want your grid points to make sense (with your temporal resolution and number of taxa).

- In Skygrid, you are not guaranteed to have at least one coalescent event per time segment. If not, those populations are not going to be identifiable.

- If you are worried about over-smoothing, you should check out the Omega formula from Parag, et al.